.jpg)

Unfortunately, examples of poor communication are everywhere in business. Recall the time you asked your coworker a simple question, only to find yourself trapped in hours of Zoom Meeting Hell. Or when you had to squint at a PowerPoint because someone tried to squeeze what looks like War and Peace onto a single slide. Or when a business partner pinged you to ask whether “that project is done yet” without bothering to specify which project “that project” happened to be.

Dealing with poor communication is infuriating. But while unscrupulous politicians and salespeople exist, I assume that most people yearn to understand and to be understood by others. In that case, there is hope. I’m convinced that effective communication can be readily taught.

The following is my list of principles on how to communicate clearly and effectively. Use them liberally: apply them when you craft your memos, conversations, emails, and presentations. If you want to improve as a communicator, these rules are for you.

First Principles

1. Start With the Right Mindset

Success at any meaningful endeavor begins with having the right mindset. When it comes to a communicator’s mindset, Stephen Pinker states the following in his book The Sense of Style:

The key is to assume that your readers are as intelligent and sophisticated as you are, but that they happen not to know something you know.

In other words, treat your audience with respect, and carefully consider what key pieces of information you have that they lack. Your job is to inform, not to show off how smart you are. And I hope it goes without saying that being a patronizing asshole fundamentally hurts your ability to get your message across.

2. Consider the Limits of Short-Term Memory

Now, let’s consider human psychology. In 1956, psychologist George Miller published a seminal paper on limits of short-term memory titled “The Magical Number is Seven, Plus or Minus Two”. The key insight is that while long-term memory is effectively infinite, your ability to learn new concepts is bottlenecked by your short-term memory. Miller finds that the maximum number of ideas you can hold in your short-term memory at a given time is somewhere between five and nine.

Miller’s finding has important implications on how you should and shouldn’t communicate. It serves as the scientific rationale behind several of the rules that follow.

Things To Do

3. Clearly State Your Topic and Explain Why It Matters

Your audience needs a reason to listen to you. If they have no clue what you’re talking about, then they have no reason to care. If they have no idea why it matters, they also have no reason to care.

4. Present Your Ideas In a Manageable Number of Chunks

Since short-term memory can only hold 7 ± 2 ideas at a time, you should carefully consider how you group your information and how much of it you should introduce. When multiple pieces of information are grouped into a meaningful “chunk”, they only take up one spot in short-term memory. For example:

-

A random sequence of numbers such as 8-6-7-5-3-0-9 is difficult to remember because it consists of seven discrete pieces of information.

-

Written as a US phone number, and 867-5309 becomes two chunks.

-

Turn it into the chorus of a catchy song by Tommy Tutone, and you’ve compressed the string of numbers into one single chunk.

A stream of consciousness or a wall of text does nobody any favors: there are too many individual pieces of information to fit into short-term memory. So consider:

-

Chunking the information, and

-

Only introducing a small number of chunks at a time.

If you have a presentation slide with too much text, consider distilling it into a handful of bullet points. When you speak, introduce your ideas in a meaningful sequence, and strategically punctuate your speech with pauses to denote groupings of ideas.

5. Introduce Hierarchy to Your ideas

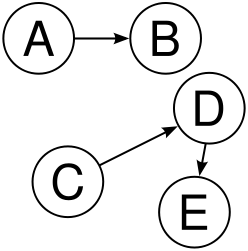

Information in the wild has no order; you can imagine them as randomly floating in the ether. During the process of crafting a narrative or explanation, you form connections between pieces of information.

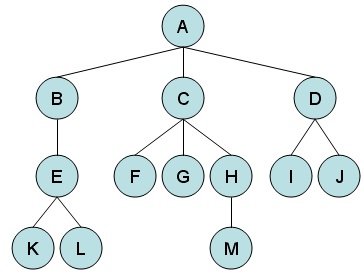

Drawing connections is necessary but insufficient; you also need to organize and prioritize your info. Which are the main points you’re trying to get across, and which are auxiliary ideas or supporting evidence? When you introduce both connections and hierarchy to your ideas, they take the shape of a tree.

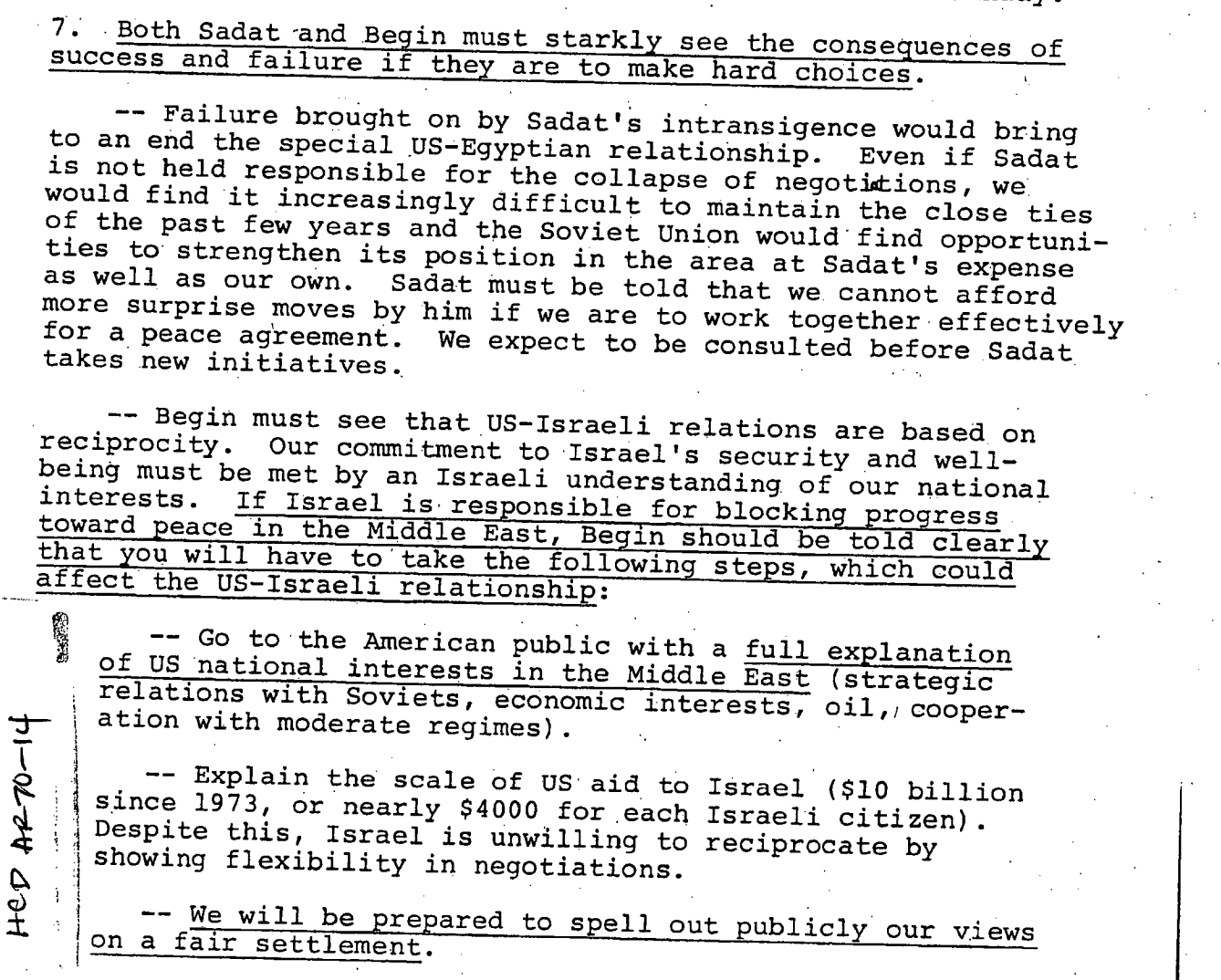

Explanations with tree-like hierarchy are clear and easy to understand. Consider Zbigniew Brzezinski’s 1978 memo to President Carter on how to moderate negotiations between the leaders of Israel and Egypt. This memo has been lauded in Forbes as the “greatest memo ever”. In the memo’s five terse pages, you can clearly see the hierarchical layout of Brzezinski’s main points (marked with numbers) and supporting arguments (indicated by dashes and a progressively larger number of indents). For example:

Organizing information into hierarchical structure requires hard work, but the work pays off many times over. In Brzezinski’s case, President Carter heeded his advice and used it to successfully broker the Camp David Accords.

6. Stay Focused on High-Level Ideas

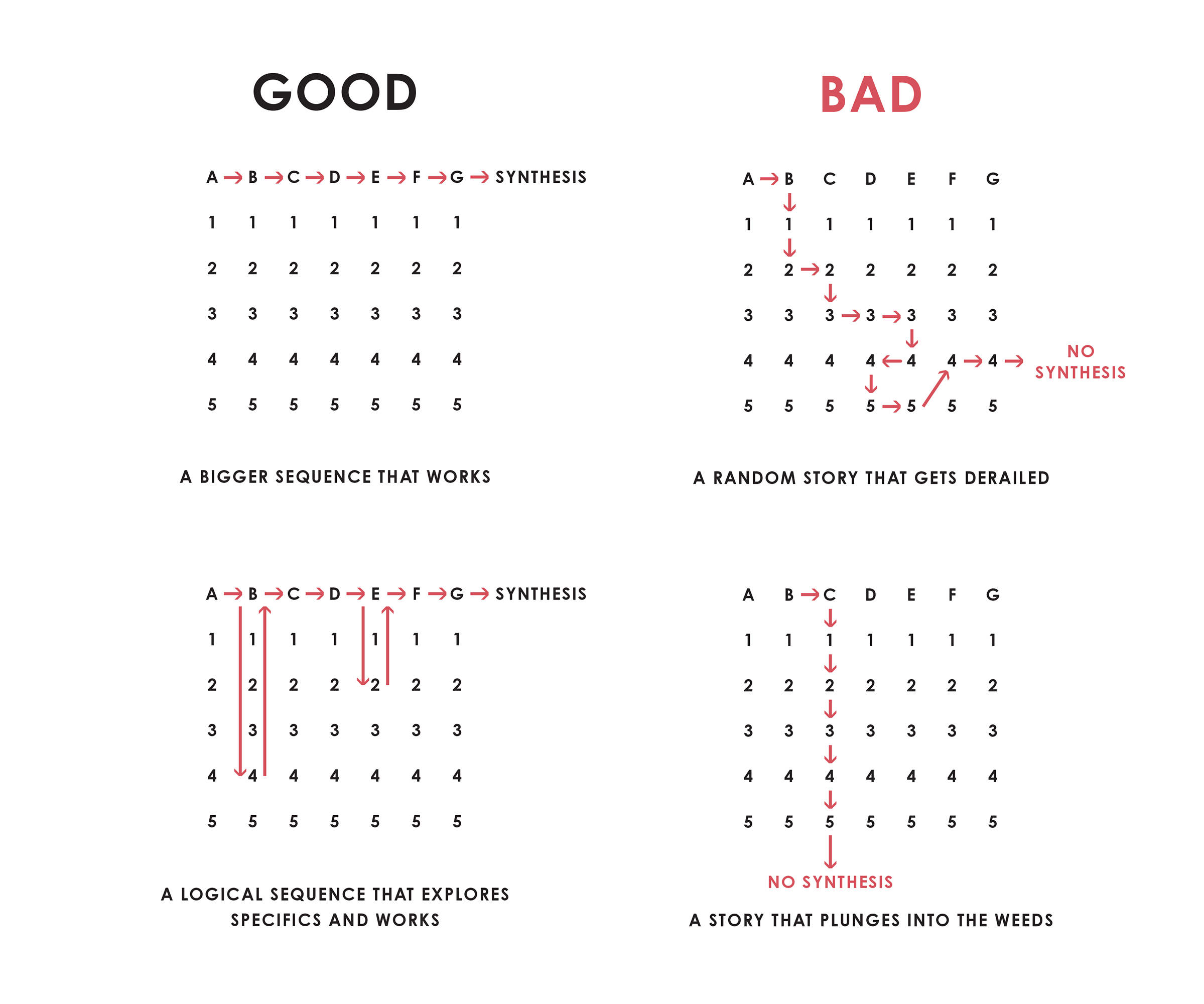

When your information is organized in a hierarchy, it’s easy to tell the difference between high-level ideas and details. You need to convey the high-level ideas in every conversation related to your topic. How much you want to dive into the details will depend on if you’re giving a regular elevator pitch or if you’re trapped in that elevator with Elon Musk.

In his book Principles, Ray Dalio uses the following four illustrations to demonstrate what it means to stay focused on the high-level.

7. Use Visual Aids When Things Get Complicated

See what I just did there? A picture is truly worth a thousand words.

Things to Avoid

8. Reduce Your Use of Acronyms

In A Brief History of Time, Stephen Hawking explains that his book on astrophysics only contains one equation (E = mc2) because “each equation [he] included in the book would halve the sales.” In the same spirit, I offer this rule-of-thumb: each acronym you use halves your potential audience.

Suppose you work for a large corporation, and you’re giving a presentation on cloud computing to a diverse group of stakeholders. Don’t automatically assume your audience knows that an “ASG” is an “Auto Scaling Group”, or that “EC2” stands for “Elastic Compute Cloud”. Carefully consider whether they do before turning your presentation into an alphabet soup. Or better yet, either spell out the actual words or ditch the jargon in favor of simpler language.

9. Don’t Force People to Perform Mental Math

Please, please, please don’t do this. Few things terrify me more than when people force me to crunch numbers in my head when I’m already confused by what they’re saying. This is possibly the worst way to clarify a difficult concept.

Mental math operations are costly: recall that a person’s short-term memory can only hold five to nine chunks of information at a time. If I need to prove to myself that 448 is roughly 5% of 8,966, that feat of arithmetic takes up at least three spots in my short-term memory (and likely more since I’ve never been good at mental math). That’s valuable real estate that could have been used to hold information that’s actually relevant to understanding the concept at hand.

If you must use numbers to prove a point, write out the math on a whiteboard or huddle around a spreadsheet. I guarantee you that forcing listeners to perform mental math will not help them understand what you’re saying.

Header photo by Charles Deluvio on Unsplash